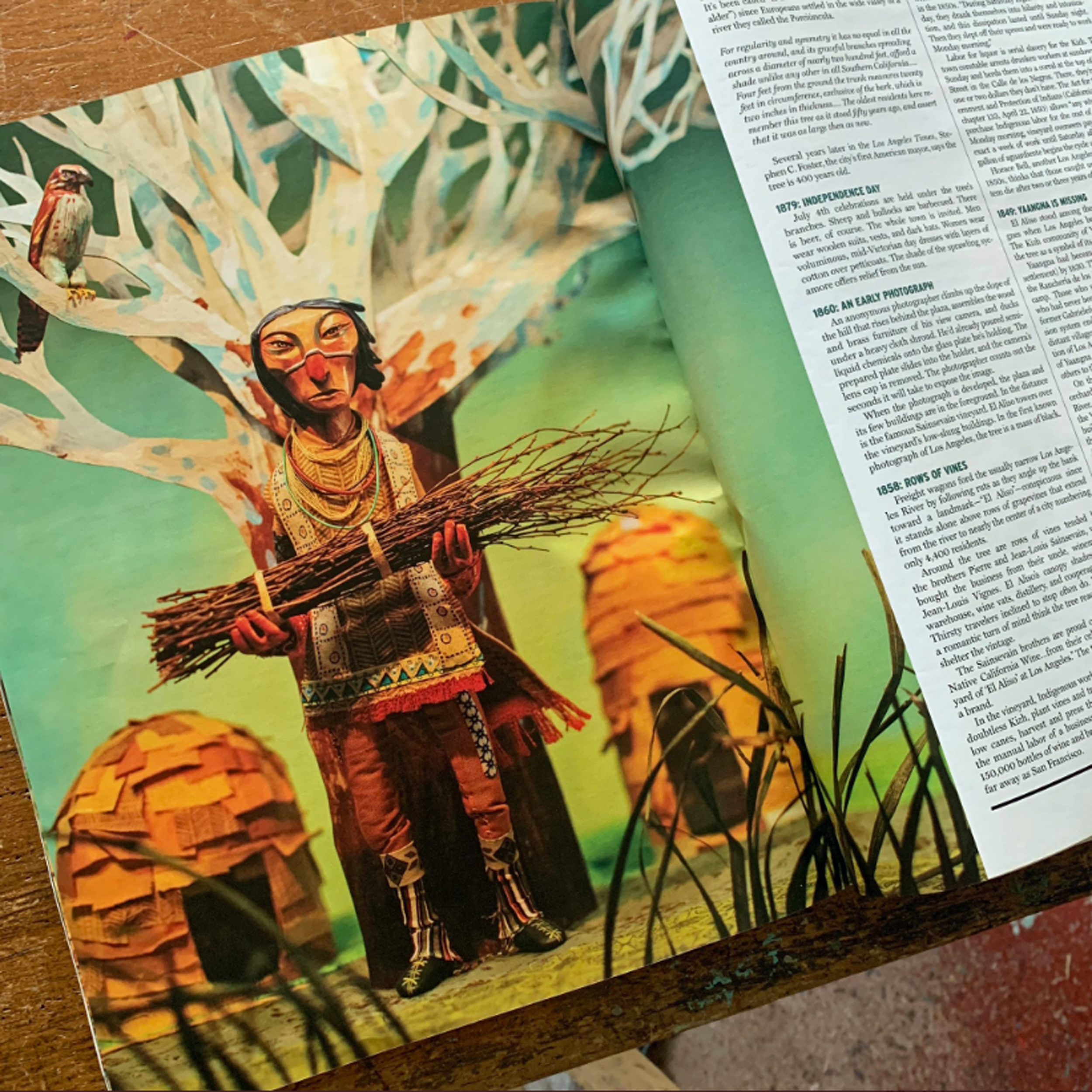

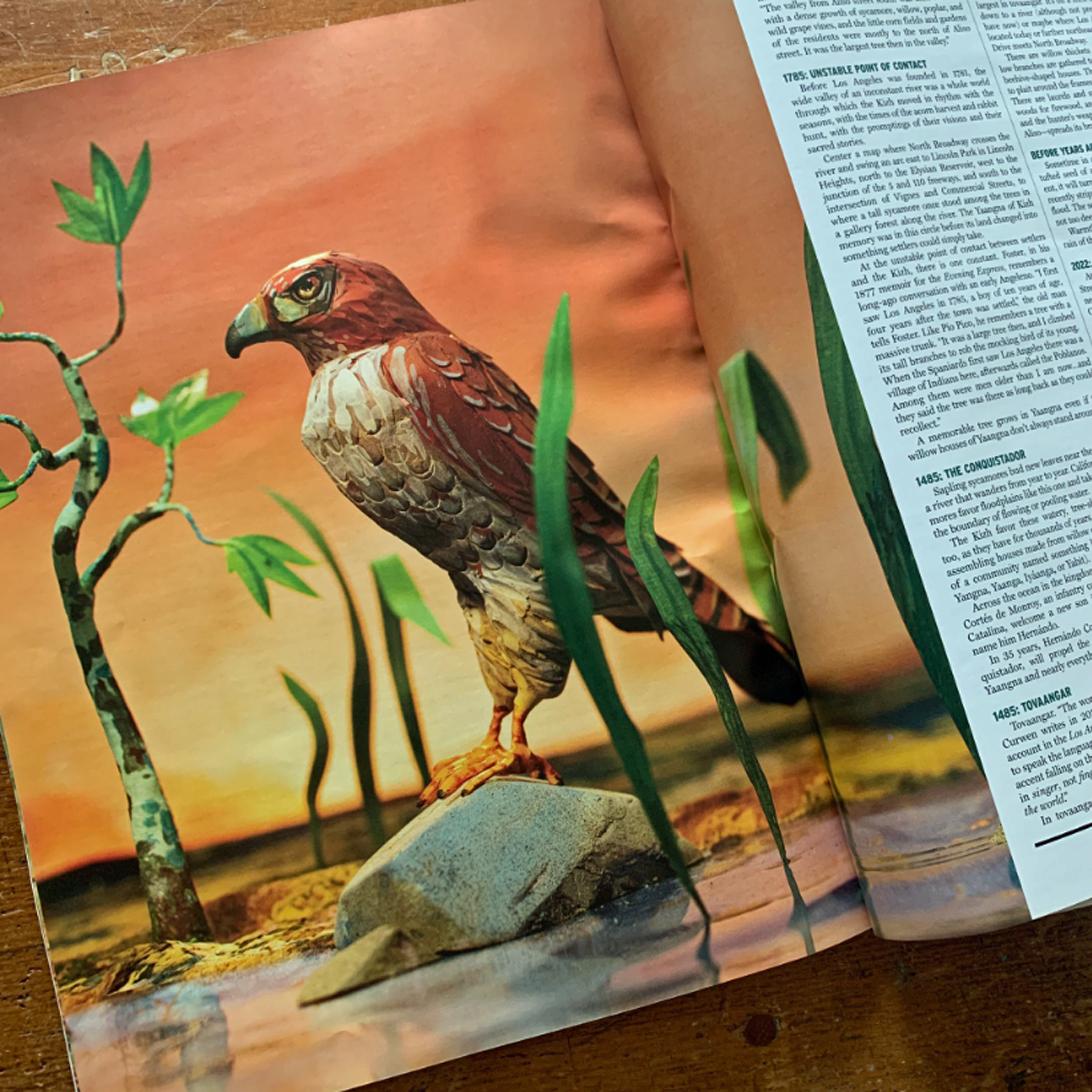

El Aliso

Deep Roots in Los Angeles History

El Aliso

Deep Roots in Los Angeles History

Illustrations by Chris Sickles | Red Nose Studio

This story is told from its end to a beginning. It’s about a remarkable tree now gone, but even more, it’s about a place also lost. Places that are lost are the most precisely located. They’re found in memory.

Facing the Facts

From Close to Home: An American Album, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004

Facing the Facts

From Close to Home: An American Album, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004

House: Photograph by Tom Johnson

Everything's mine but just on loan, nothing for the memory to hold, though mine as long as I look.

- Wislawa Szymborska

REMEMBER? You were young and holding a paper rectangle as crisp as a playing card, its surface like glass, and behind the surface, someone posing for a picture. Then a woman's hand, far older than yours, passed you another snapshot. "This is my aunt and here is her husband," she said. "You never met them because they lived back east." (Everyone you never met lived there; you thought "back east" must have been a place filled with abandoned, disoriented people.)

"Let me tell you their story," she continued, and she does, but it's only a fragment. Because here is a snapshot of your father in his Army uniform when he went to into the war, but that's only a fragment and another story. Because here you are when you were three, not so long ago and in another place, but your own story is only a fragment to you, too. Because here is another snapshot and another story. (Montage didn't begin at the movies; it began with the family album.)

Then one day, years later, the only member of your family dies who knew how to piece these fragments together. Why did she hold these stories, just as the shoeboxes held these snapshots? Why didn't anyone else hold them? Then your father dies; his wartime buddies, lean and young in their snapshots, die a second death from forgetfulness. Then your mother dies; her wedding pictures are crowded with lovely bridesmaids and a grim minister unremembered long before. But the snapshots, which had once been poised between hands like a magician's levitating card trick, remain.

You put the shoeboxes of snapshots in the garage, thinking, you do I know any of these people? But dimly, here's a face that seems familiar. Is that your mother's cousin, looking serious, the one who loved her like a sister, didn't someone once say? Is that your father's boss, smiling broadly for no reason, whose son died in Vietnam? Still later, you took the shoeboxes to a self-storage place at the edge of town because you've got so much stuff at the house and the garage is full already, but you couldn't throw these snapshots away. You want to turn them over to the kids, but you discover you don't have kids or they won't have you, and then you have other things to think about, now that you're dead.

A few months after, because you've passed beyond caring and paying the rent, a man you never met (from back east, perhaps) buys everything in the storage unit where the shackle of the padlock has just been cut, and he puts everything, including the boxes of snapshots, in the back of a shabby pickup or a van with patches of gray primer paint and he goes to the Saturday swap meet at a rundown drive-in movie theater to sell what he can, and some of the shoeboxes of snapshots split and spill the pictures out, and the guy who brought the boxes leaves them there all day without looking at them.

The snapshots that don’t sell by the end of the day, he'll throw in the dumpster next to the swap meet snack bar when he packs up and leaves.

But before then, someone standing in front of the seller’s stall reaches down and picks up a glossy rectangle of black and white and stares into it like a peeping tom gazing into an empty room. Your lost snapshots have been found.

Is this the fate you would have chosen for them (if you could choose anything from your place of eternal repose)? Would you have your snapshots gathered at the entrance to the incinerator of history, stripped of associations, and selected, this one to be kept for now by a knowing stranger for reasons you'd find puzzling and possibly sad, and those others—perhaps the very ones that once evoked the purest memories—to be lost forever?

Long ago, when they were in the air between old hands and your hands, your snapshots weren't ironic. They weren’t art. They didn't want more than what was told about them. They didn't congratulate the photographer who took them or the one who gazed at them. Your snapshots had only one aspiration: to be handed around. They had only one purpose: to incite stories. They had the power to appropriate and alienate—and they did—but they only intended to cherish.

Photography, as the first modern art (that is, the first to give science greater weight than aesthetics), had promised more. Photography had promised to bring back hard evidence from a world of facts, but it only delivered more conjecture. “This is the way things are,” a photograph insists, but we know by now that it's only the way something was, and only for an instant and only in one preferred direction, without reference to what was off to the side, or to the moment before, or any of the many moments that followed.

Photography had promised to romanticize everyday life, too, but the democratically simple Kodak camera of 1888, and the cheaper and simpler cameras that followed, rained hundreds of millions of casual snapshots over the nineteenth-century's uplifting assumptions about science and art. Then the Kodak System ("You press the button, we do the rest") collapsed picture taker, subject, and consumer into one—a twitchy, indiscriminate shutterbug who, from childhood on, knew how to take a snapshot and be seen in one.

Photography's document and romance became the snapshot’s incident and sentiment. The sparse vocabulary of gesture in a snapshot, recalled at the moment when everyone in the viewfinder shifts into a pose at the command of the picture taker, means that almost every picture has the same surface. Vacationers pose with their back to the sight they are supposed to be seeing. Major celebrations are always recorded as tableaus of family relationships; very few friends or colleagues make the cut. Moody children and exuberant adults are always moody or exuberant; they never break character before the camera. Self-conscious jokes re-create the compositional pratfalls of naïve snapshots, except no one is naïve anymore. More women and children are pictured; men are behind the camera, calling the shots. The first child is photographed more than the next and, according to studies of family albums, is the only one who will be shown being fed. Snapshot shooters never take pictures of family arguments, abuse by spouses or parents, the deteriorations of sickness and disability, or the facts of solitude or death.

(Today's picture takers are so squeamish. During the nineteenth century, studio photographers often photo- graphed dead children, lying as if asleep in a cradle but more often being held in their mother's arms, sometimes posed with other children in the family. In Austria, so many parents went to photo studios with dead children that the authorities declared a public health threat and prohibited the practice.)

Snapshot shooters sidestep more than just troubling content. In older photographs, the subjects look glum, partly, of course, because of long exposure times, but also, perhaps, because they were closer to an era when facts didn't come with so much cheerful spin. The faces mostly smile in snapshots—like archaic Greek kouroi or the figures of husbands and wives from Egypt's Old Kingdom tombs—because the subjects are aware that their photograph is the projection of an image as much as it's the preservation of a fact.

Today, photographer and subject, becoming each other as they hand the cell phone camera back and forth, have thoroughly internalized snapshot clichés. They've already seen the picture they've just taken. It's been parodied in magazine advertisements, accompanied a TV newscaster's announcement of a killing, appeared inside a supermarket tabloid, illustrated a dictator's biography, hung in a museum gallery, been found wedged between the pages of a library book, and been pasted into an album lying in a funeral home next to the coffin of a distant relative.

The next snapshot they're about to take is everywhere, too. Everyone makes them. Everyone's in them. Everyone wants to be remembered. Almost everyone wants to remember, but there are so many pasts: the past in private reverie, in family fable, and in public history. Pick up one of your snapshots, even one that you only half remember, and many pasts push forward.

It's the work of a moment to chuck out or incinerate a single snapshot or a lifetime of them when one of these pasts is no longer wanted. The standard black-and-white print of 1950, with its filigreed edge, rips after a slight resistance; self-inflicted amnesia couldn't be more satisfying. It's a wonder that so many snapshots have survived. But it's problematic that they'll survive as the vernacular of memory much longer. "Kodak culture" has gone digital, and the uses of the digital snapshot serve our purposes less than they do "the acceleration of history," Henry Adams's baleful insight in 1908 that, in the name of quickening modernity, we're bound to be barbarians to ourselves. Few digital snapshots will have anything like the durability of the drugstore print of sixty years ago.

By leaving fewer tangible traces to provoke a story, our past is becoming the past ever faster. To gain even more speed, we lighten ourselves of the snapshots by which we remember, especially when the traces of memory are so commonplace, so unflattering, and so much in need of us. What's thrown overboard in the regime of speed is mostly sucked under and lost. But some of it washes up on a distant, asphalt shore.

Nativity

You survived because you were the first. You survived because you were the last.

Because alone. Because the others.

Because on the left. Because on the right.

Because it was raining. Because it was sunny. Because a shadow fell.

- Wislawa Szymborska

Randy Burger is a friend who, on weekends, combs a swap meet in a community-college parking lot. It's the sort of swap meet where you find working-class vendors selling to the working poor. Professional dealers in the things auctioned from storage units come, too. They lay out stuff sifting downward in an informal economy that processes the lost bits of everyday life after the obviously valuable and usefully secondhand and minimally collectible are mostly, but not entirely, gleaned for a profit before the swap meet opens. At the bottom of the swap meet economy, my friend says, are the family snapshots.

He isn't looking for lost photographs—he calls them "orphaned"—but he sees a lot of them anyway. "I once saw an album," he tells me, "that was filled with old photographs and it was carefully annotated, including genealogies." (A whole tribe obliterated.) He says that photographs still in frames are sold for the value of the frame. Loose snapshots sell for next to nothing; vendors will give them away. "I can only hope that the moment when one of these photos was taken was a moment filled with genuine feeling," he says, "and that the photo and what it represented were cherished and understood by someone," even if it was only for a little while.

He sees his own future. "I don't know all the people in my own photographs—relatives or friends of my parents who stand around smiling in front of houses, in front of cars, and in front of tractors," he says. "What I do know probably won't last another generation. Not only can I see the faces of my relatives one day looking up at someone at that swap meet, but I can see my own face frozen in time on the asphalt of that parking lot." My friend grieves over what he expects to be. "You and I saw a tombstone years ago in Quebec City," he reminds me. "Ne m'oubliez pas,” it said. “Don't forget me.”

The commandment to remember leads some to collect and publish their found snapshots as acts of resistance against official amnesia. At Susan Meiselas's website, stateless Kurds are asked to identify a growing collection of anonymous snapshots to "build a collective memory," she says, for "a people who have no national archive."

Ann Weiss found the photographs of an even more monstrous forgetting. She walked into a neglected storeroom at Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in 1986 and found nearly three thousand snapshots collected in 1943 by Nazi guards from a trainload of Jewish prisoners. Lest the fact of their life outlive their death, the prisoners’ snapshots were routinely destroyed, except for these that escaped and were later confiscated by the camp's Red Army liberators, kept by them for no apparent purpose, and then returned to Auschwitz-Birkenau only to be forgotten again. Weiss spent years restoring names to her found snapshots, giving stories to mundane pictures of weddings, birthdays, summer outings, sober people holding babies, businessmen in suits, and smiling women in hats.

By what they had chosen to remember, these men and women had restored to them a life uncontaminated by the terrible abstraction of their death. This is the heroism of snapshots: in the right hands, they stand against the evil of enforced forgetting.

And if they aren't dumped by the end of the day, and if they fall into avid hands of a collector by chance, then lost snapshots found at the swap meet become objects of fascination. "My personal reaction is different each time I find some," Ann Colvin, a collector, tells me. "They catch my eye, the time period mostly, then I just get lost in the 'looking.' The photographs always have stories. Some are obvious, like old wedding photographs or events in a family's life, and some are hidden in the photography itself. Those I find most interesting, and they draw me into them. Again, I find myself lost in the image. I believe they can become almost magic."

Colvin hangs her snapshots where her friends and family members see them and ask about them. Other collectors assemble their found snapshots in online galleries where the viewer's speculation is invited. This is mostly comedy with ironic captions, but sometimes a found snapshot fulfills its purpose as the pretext to a story, even if the story isn't the snapshot's own.

Gail Pine and Jacqueline Woods—California artists who are custodians of thousands of photographs rescued from swap meets—tap into this mystery. "Memory, an intangible, seems almost a tangible thing," they assure me, "when gazing into a snapshot. Suddenly smells, sounds, and sometimes even tastes bump us right in the memory bone. The 'Then' becomes 'Now,' just for a second."

Found photographs are elusive, vulnerable, ominous, and ordinary, part historical diorama and part freak show. Mutely, they've passed through hazards to be selected, each with its own practical, moral, and aesthetic questions: Why was that subject photographed and that snapshot printed and that one saved? Why was this snapshot picked up before others were thrown away, that one chosen later to be kept when others weren't? And-for a very few, why were these snapshots delivered to the museum curator, and why did some of those make the cut and get on the gallery wall?

I don't know. All I know is how to look. All I see is how one photographer once saw. The longer I look, the more the snapshot in my hand becomes anything I want to make of it.

Maybe this particular photograph is folk art. The nicely dressed man and women displaying a birthday cake, the boy padded with rats, the woman dressed as a die, and the man in the "Groucho" glasses and mustache insist on the validity of their representation of themselves. "I made this of me," they might be saying. "For my own purposes."

Maybe found snapshots are just uncanny: an American-brand surreality of domesticated weirdness plucked by the disembodied wit of modernity from the chaos of the images we've made of ourselves. The very tall man and the very short woman dance on the lawn. The two women grimace while another looks on. The car enters the car wash. The nearly empty refrigerator gapes to reveal a can of V-8. The woman in undergarments and stockings hoists a double highball glass. The woman in a bikini holds a dead rabbit and a rifle. The woman in the sunsuit does a stock pinup pose under a sign that reads "PRIVATE." The baby holds a picture of a soldier.

Or maybe this found photograph is something else entirely. The simple drugstore print buckles under the weight of interpretation even as I begin to understand that the interpretive impulse is all that I have in the face of the snapshot's obdurate presence. Found snapshots may look like fragments of a narrative to be decoded, but the formal grids I lay over them never stick.

All I do is look. I'm a voyeur, a stranger who should never have been left alone to thumb through the family album and become fascinated with intimacies that were not meant for me.

The couple in the embrace of the light that hovers over them is smiling so calmly that I want to be their son. His right hand on the back of her upholstered chair is the promise of a touch. If the radio begins playing something sentimental, he might complete his half-turn around the lamp, lean on the wide arm of her chair, and give the matronly woman—her smile is more knowing, now that I think about it—a young man's kiss.

The voyeur's pleasure is your exposure to his daydream and his concealment from you. Putting snapshots in the museum validates and regulates my voyeuristic looking-from-a-distance at a photograph's nakedness. Although the intimate moments are curiously dispassionate and everything in the image is on the surface, the found snapshot on display in "the context of no context" on the white gallery wall gains for me unintended erotic attraction.

In traveling from closet to museum, snapshots shed their role as instigators of domestic history—always partial and subject to revision—and became, for their viewers, objects of wonder or harmless prurience. For photographers, they became a source catalogue for an accidental "snapshot aesthetic" of the irrelevant and unintelligible details that dominate a photograph when the narrative of everyday life is stopped with a click. In the "authored" snapshot photography in the 1970s and 1980s, the snapshot's mixture of contrivance and vulnerability lent a fleeting authenticity to the photographs in museum shows and magazine spreads. "Look at this moment," invented snapshots said, "but you miss the point if you regard us too long or too seriously. And remember to look ironically."

Museum curators, the official custodians of what we look at, have hung both found and made-up snapshots next to crime scene photos, stills from industrial films, pornography, mug shots, accident investigation records, and institutional photography. They used snapshots, among other ambiguous objects, to make a new kind of museum out of the deconsecrated space that was left after the passing of modernism.

The swarm of ambivalent meanings in found snapshots (and in other anonymous or almost anonymous photography) has conveniently answered everyone's needs, from commodity to fetish to consolation.

Yard Sale

Memory at last has what it sought.

- Wislawa Szymborska

Found snapshots serve the memory of modernism with their artless gestures toward the themes of the old avant-garde. That makes them chilling fun when they're at the safe distance of a gallery wall or in the pages of a coffee-table book. But what demand is made by the hunger of memory in them?

It might be compassion. Snapshots litter the contested ground between candor and concealment, between what's public and what's private. Imagine everyone gathered around the family photo album. The snapshot in view, depending on who's doing the looking, is horrifying, hilarious, pointless, or suffused with yearning. What a snapshot wants to have leak out of its neat rectangle is the messy network of human relationships from which the snapshot was made.

Or the hunger might be fear. All of us are arsonists, and the ordinary is on fire every day. These snapshots—those you've just found at the swap meet and your own that you're about to lose—insist that we're destined to be among the disappeared. The flimsy snapshot is the last artifact that will remember your likeness and your unavailing self-regard. What a snapshot fears isn't its destruction but your anonymity.

"We are poor passing facts," wrote Robert Lowell, "warned by that to give / each figure in the photograph / his living name." It's tenderness, then, for which your snapshots yearn. It's not just the faces in a snapshot that appeal for a caress that cannot be reciprocated. Everything in the snapshot wants it, and all the much-handled things you grew up with want it, too. "Fall in love again," your snapshots say, "with what you already have."

Or these snapshots might need your forgiveness. Grievances crowd them, even the snapshots that aren't yours. Either they fail to satisfy your present desires and leave you with fury and contempt, or they record desires you no longer want. That does not make them less in need of you. In fact, the more worn and undecipherable the image, the more it resists our easy dismissal, and the more it insists that its references be puzzled out, its story be imagined into existence. The purpose in a found snapshot is, I suppose, to teach you pity and give you a human heart.

Or it's just to persist. The commonplace, the place where we find love and hope, necessarily disappears without a murmur or complaint; it's only remembered. The snapshots I hold resist my preference for forgetfulness.

We're like snapshots. What we hunger for is remembrance. Found snapshots are trivial, but they're bodies, too, just like you and me, and they have nowhere else to go but into someone's hands or into the furnace. You are seeing. They are seen. That's all the faith they need. Just look. You were lost, but now your snapshots have found you.

------------------------------------------

“Facing the Facts” was the essay accompanying the exhibition catalog for Close to Home, presented by the J. Paul Getty Museum October 12, 2004 to January 16, 2005 at the Getty Center. Snapshot photography has changed dramatically in the nearly 20 years since the exhibition, but the cloud of meanings and apprehensions in snapshots—digital and analog—still clings to them.

The photographs in this essay are snapshots by photographer Tom Johnson and are used by permission.

Ideal Los Angeles

The Stahl House

Ideal Los Angeles

The Stahl House

Pierre Koenig's Stahl House (Case Study House #22) epitomized the ideal of modern living in postwar Los Angeles.

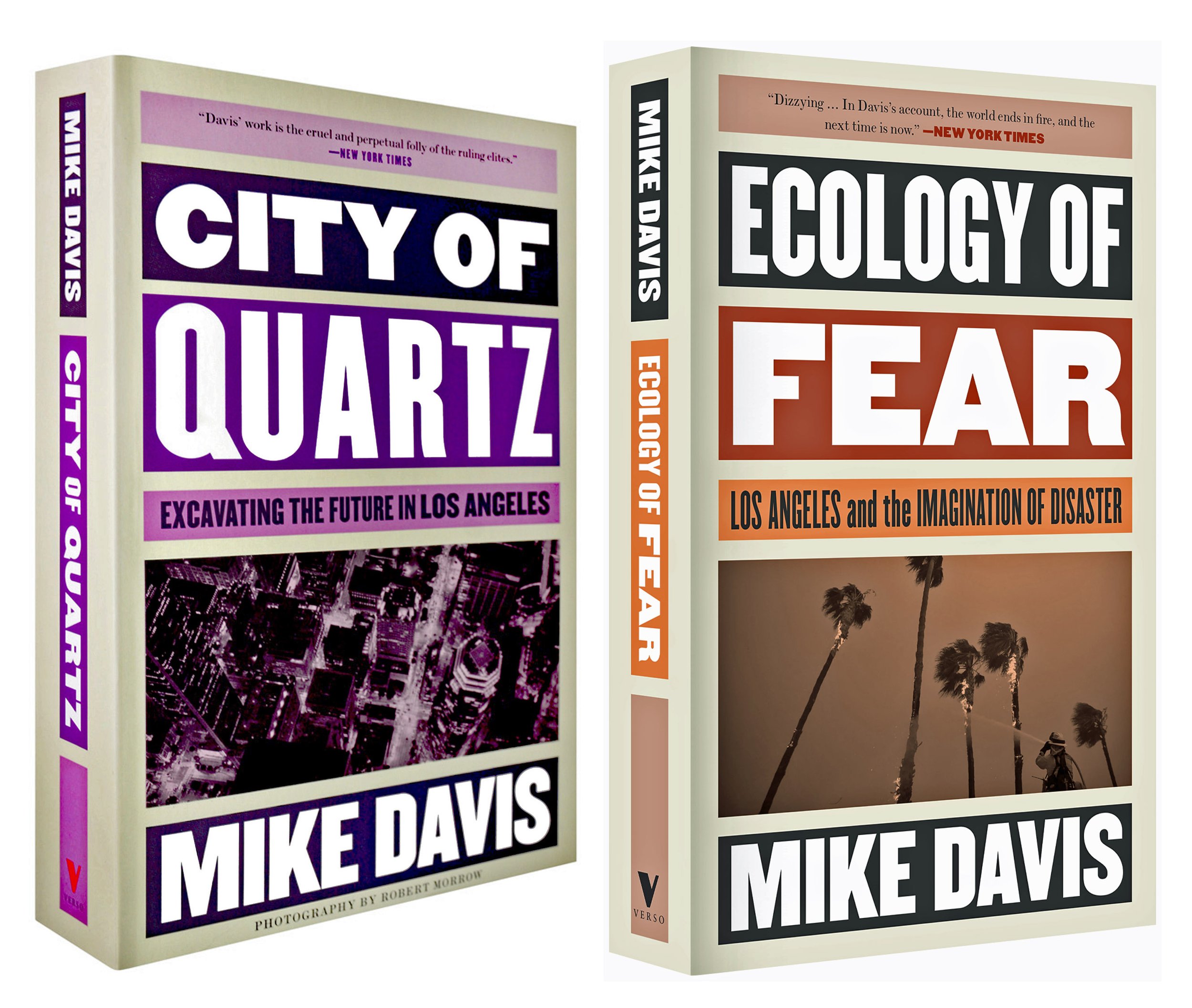

Mike Davis: With Anger and Love

He showed Angelenos who they were.

Mike Davis: With Anger and Love

He showed Angelenos who they were.

City of Quartz (1990) and Ecology of Fear (1998) demolished booster clichés about Los Angeles.

Prologue

I met Alessandra Moctezuma the other day at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art. Moctezuma is Gallery Director and Professor of Art at San Diego Mesa College, where she leads the Museum Studies program and teaches courses on Chicano/a art. She is also the widow of historian and social critic Mike Davis who died in October 2022. We chatted briefly after I offered what condolences I could for her loss and ours.

Shortly after his death was announced, I reflected on Davis’ achievements as an interpreter of Los Angeles in a brief essay for the Los Angeles Times. That essay—somewhat revised—is offered here.

With Anger and Love

We’ve lost Joan Didion and now Mike Davis. Kevin Starr preceded them in 2017, but these three interpreters of our coast of dreams should be read together. They told us who we were as Angelenos and, more broadly, as Californians. Davis was a thorough Marxist. Didion was the flinty realist. And Starr was Catholic. Each had a theory of history—an explanatory model of the forces that had made Los Angeles and brought us, sometimes heedlessly, to it.

Davis and Starr were friends (an irony that delighted Starr), perhaps because both believed that history inevitably aims toward a redemptive conclusion. Both Karl Marx and Thomas Aquinas thought that history would have a happy ending, however delayed it might be.

In service to that conviction, Davis examined the distempers of Los Angeles and diagnosed their causes. His analysis was often harrowing. I criticized him for his conclusion (in Ecology of Fear) that my working-class neighbors should never have been allowed to live where they still do, that their hopes for an ordinary life had cruelly deceived them.

In an interview Davis gave to the Los Angeles Times in July 2022, he disparaged the idea of hope. “I don’t think hope is a scientific category. And I don’t think that people fight or stay the course because of hope; I think people do it out of love and anger.”

Mike Davis: Scholar, Activist

“Love and anger” are the fires that burn through his books, though I cannot judge the proportion of anger to love. Despite Davis’ reputation for bleakness, I prefer to believe that eventually love was dominant. He told the Guardian newspaper in August 2022, after he had ended treatment for esophageal cancer, “What keeps us going, ultimately, is our love for each other, and our refusal to bow our heads, to accept the verdict, however all-powerful it seems.” “Fight” was a word Davis often used.

This is a “romantic” imagination—the imaginative faculty that that makes alternative histories plausible and even achievable. Davis begins his most celebrated book—City of Quartz—in the ruins of Llano del Rio, a utopian community founded in 1914 by Job Harriman, who could have become the first Socialist mayor of Los Angeles. His campaign was wrecked by the bombing of the Los Angeles Times in 1910 and by his defense of the bombers, both of them union organizers. The ruin of Llano del Rio and Job Harriman’s Socialist campaign are historical facts, but so is the engaged activism that brought both into being. Looking to the past in Los Angeles is not only instructive; it’s fortifying. Unfortunately, history has never meant much to Angelenos.

He thought his own past had value. He told author Mark Dery in 1996, “One of the things I've increasingly ended up fighting for, where I teach and in the kind of politics I do, is a nostalgized vision of what Southern California was like 30 years ago—the freedom of its beaches and its cruising streets and the kind of careless, libidinal adolescence that used to be possible.” But those “relative freedoms,” Davis knew, were exclusive. They were “the intoxications” that white kids had, which for Davis included a mild amount of hooliganism. Davis insisted that there should be other possessors of those freedoms and ultimately of what it means to be an Angeleno.

Davis wrote what he said were “impassioned polemics on the necessity of the urban left.” He was less convinced of the necessity of the sacred ordinariness my neighbors had exchanged for class consciousness.

Davis wanted action, not murals or marches. He said he didn’t want to die quietly but on the revolutionary barricades somewhere “with the red flags flying.” Instead of a revolution, Davis gave us a different way to see Los Angeles by demolishing not only the city’s endemic boosterism but also the clichés of sunshine and noir that the city’s critics still deploy. His scholarship cleared a wide space in what can be said about Los Angeles, a place where divergent stories—from the streets and in neighborhoods—could be told by a multitude of other voices. I was fortunate to be one of them because of Davis.

“People’s stories are key,” Mike Davis said. “Listen carefully to the quiet, profound people who have lost everything but their dignity.” He passionately believed that shared and remembered stories create communities and sustain lives. Joan Didion and Kevin Starr had a similar faith in narrative. As interpreters, these three showed Angelenos who they were. But now they’re gone.

If Los Angeles—so beautiful and tragic—means anything to Angelenos today, they’ll have to find and fiercely embrace (and just as fiercely question) new interpreters who will help them see who they are now.

Walking in LA

Los Angeles is the second-most dangerous city for pedestrians in the U.S.

Walking in LA

Los Angeles is the second-most dangerous city for pedestrians in the U.S.

A dangerous place to be in Los Angeles

I don't drive, though I grew up and still live in suburban Los Angeles. I don't drive because of the effects of glaucoma and keratoconus on my eyesight and the loss of effective vision in my right eye. If I could, of course I would drive. The swoop of a freeway onramp and the intoxication of momentum are this city’s birthright.

I’m not part of the Los Angeles that drives. I’m the part that’s driven.

When I tell people in Los Angeles that I don't drive, they express mild surprise. Some assume that my non-driving is an environmental statement. When I tell them I don't drive because I don't see well, they become skeptical. Few Angelenos can imagine that an otherwise fit-looking, middle-class male would not drive, however marginal his vision.

Drivers are uneasy with my claim of disability. Maybe they think it's something they’d prefer not to hear that keeps me from driving.

Instead, I talk briefly about taking the bus. They’re uninterested. I'm describing habits drivers have no intention of ever acquiring. They imagine a future in which they will always be drivers. They think they will always be in control, if only of a car.

I'm lucky those drivers have been so willing to tax themselves for the past 40 years to expand a transit system few of them will use. I'm luckier still that I can be in the company of bus riders far from my home with no certain way back, trusting their knowledge of the route they'll willingly share.

Instead of driving a car, I get lifts from friends. I'm a good passenger. I don't reflexively apply a phantom brake if the driver doesn't respond fast enough to slowing traffic. I don't presume to know the directions to where we're going. I don't question the driver's choice of lane, speed or off ramp. I don't ask to have the radio or air conditioning on or off.

■ ■ ■

Like Ray Bradbury—who was a Los Angeles non-driver—I've been stopped by a patrol car on a completely empty stretch of suburban sidewalk, at midday, dressed in a coat and tie, and ordered to identify myself and explain my destination. As a pedestrian, I’m a suspect.

I’m a good pedestrian however, staying within the marked crosswalks and never jaywalking, even when the next crosswalk is a long walk away. Free-range pedestrianism is dangerous, Anti-war activist Jerry Rubin was struck and killed in 1994 while attempting to cut across Wilshire Boulevard in Westwood. The head of the Los Angeles teachers’ union, crossing the seven lanes of Olympic Boulevard, was killed.

Fewer streets are marked by crosswalks today. The city has sandblasted away hundreds since the mid-1970s when traffic engineers showed, not surprisingly, that more pedestrians are killed in crosswalks than out of them. The engineers said the painted lines gave pedestrians a false sense of security, making them less attentive to danger. Risk managers had another reason to eliminate crosswalks. Their presence makes cities vulnerable if the city is sued by injured pedestrians or their survivors.

Using a crosswalk has other risks. In 2010, a Swedish hip-hop artist punched, kicked and drove over the body of a pedestrian, killing him, because the pedestrian had asserted his right-of-way in a crosswalk.

■ ■ ■

Seen from curbside, driving looks like a pathology—a syndrome of sudden tics, cognitive agnosias and kinetic preservations.

A driver preparing to turn right on red swivels his head to the left when he's a hundred feet from the intersection. He fixes his gaze on the flow of oncoming traffic. He barely slows until his bumper reaches the leading edge of the crosswalk, his head still rotated 75 degrees to the left. If there’s a break in traffic, he continues his turn before he, for the first time, sees preparing to cross as the traffic light turns green.

I've been watching him, because traffic safety trainers tell pedestrians to stare at drivers who've turned away during a right turn maneuver. The theory is that human beings are quick to sense when someone is staring at them—a common primate threat behavior—and a driver who's stared at will react unconsciously as if the pedestrian is real. My belief that staring actually works is my only protection.

Though I've not yet stepped off the curb, some drivers slam on their brakes when our eyes finally meet. The rear of the car humps slightly while some of the slack goes out of the driver's shoulder belt. Other drivers will swerve as they complete their turn through the intersection, their eyes averted from mine.

My gaze got under the driver's second skin. I've brought the sidewalk inside his car, and he, in momentary discomfort, recognizes what I am. I rarely make out the driver's expression but sometimes I see a face that shows irritation and occasional anger.

The driver making the turn is alone. His windows are rolled up; the air conditioning and radio are on. He's cocooned inside, but he's also extended a phantom skin to the surface of his car. A neurologist would say that the driver has enlarged his proprioception—the background sense we have of how we're oriented in space and where self leaves off and not-self begins.

If a driver should ding his car in the parking lot or thump the roof going under a low branch, his expanded proprioception will make him wince as if his real skin, not the amplified surface of his car, were at risk.

■ ■ ■

Even going nowhere, your car is the room you may not have had as a child. It's one of the few places in which you can be entirely alone by choice. Driving is performed in public, but it's a private act, removed from the spectacle of the street.

When I watch from the curb, drivers seem oblivious, wrapped in a second skin of high impact plastic and sheet metal edged in shining chrome. We who do not drive are equally remote from you who does. We’ll never know the concert of speed and solitude in which drivers commune.

We're the ones at the periphery of your gaze, standing in a cluster at the intersection where you've just turned right without even slowing. As you turn, the most anxious one among us, who had been peering into the oncoming traffic for a bus that's 20 minutes late, abruptly steps back from the curb, a bulging plastic bag digging a red band into the flesh across the back of the hand she had thrust through the bag’s handle. (That red line across a numbed hand is the pedestrian stigmata).

The most resigned one of us has been hanging back, leaning his left shoulder against anything (the light standard, the stucco wall of the strip mall, a struggling tree), his head down and hands jammed into the pockets of a drooping hoodie. As walkers in Los Angeles, we are in silent attendance on the traffic bunching and flowing in its minute-long pulse as the traffic lights change.

The preoccupied drivers automatically surrender to the momentum of driving. Trust passes from driver to driver in a wheel of cars. Not one of us at the curb observes with anything like the exaltation it deserves the arc of turning cars, as lovely and orderly as the advancing line of dancers in a corps de ballet.

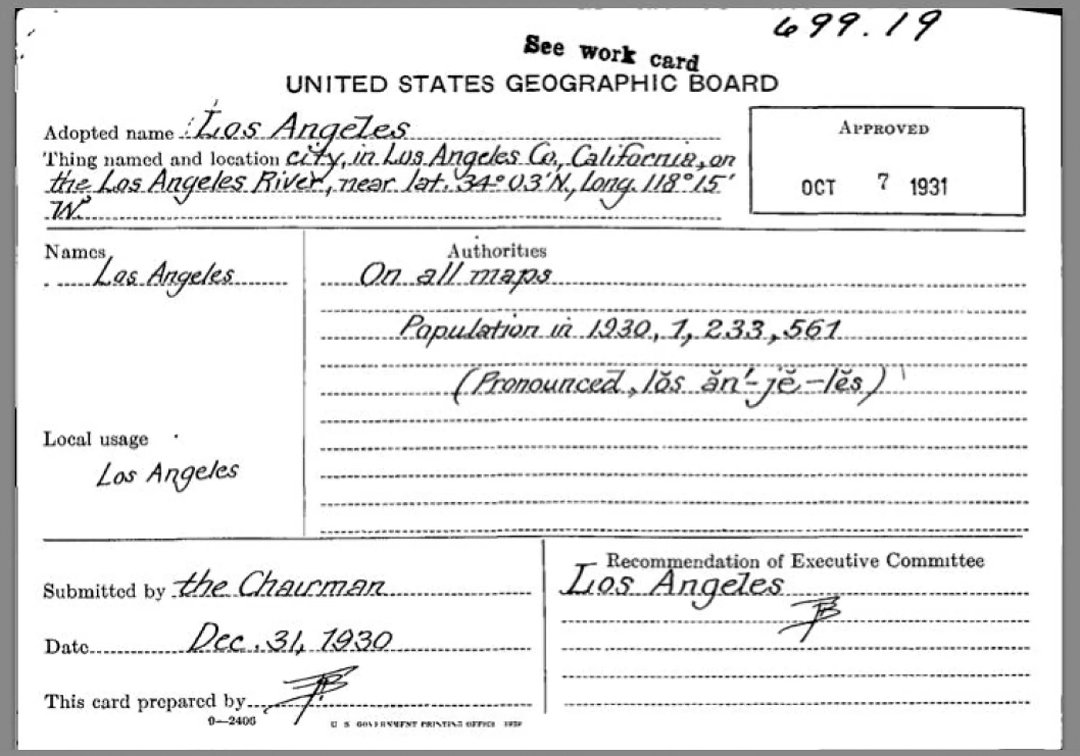

Who Do You Say I Am?

The question of the best way to name the people of Los Angeles digs into myth, history, and self-image.

Who Do You Say I Am?

The question of the best way to name the people of Los Angeles digs into myth, history, and self-image.

The US Geographic Board made the Anglo pronunciation of Los Angeles official in 1931.

Prologue

Patt Morrison, writing in the Los Angeles Times recently, surveyed an old argument: What exactly are we to call ourselves? There are several options and a few common usages. It’s not an important argument, but like many concerns that seem of interest only to historians, what we’ve called ourselves says something about what we’ve made of ourselves.

Angeleño, Angeleno, Angelino

According to the Immortales of the Real Academia Española, we’re angelinos.

The emblem of Spain’s royal academy is a refining crucible, wreathed in fire, with the motto Limpia, fija y da esplendor. The RAE has been purging, pinning down and burnishing Spanish since 1713. Its language fixes became royal decrees in 1844. Today, the academy continues more democratically to wrangle into order the grammar, spelling and vocabulary of Spain and its former colonies.

We became angelinos because of basketball. When the Los Angeles Lakers signed the Catalán forward Pau Gasol in 2008, Spain’s sportswriters needed a ruling on what to call Los Angeles basketball fans. It was unclear if they should be angelinos, angeleños, angelopolitanos, or some other gentilicio (which in Spanish denotes a people).

The rapid response unit of the royal academy—the Fundación del Español Urgente (Foundation for Emerging Spanish)—picked angelino, a gentilicio in Spanish dictionaries and already used by Spanish-speaking residents of Los Angeles to name themselves.1

America doesn’t have an academy for fixing its language like the RAE, but it did have H. L. Mencken—journalist, curmudgeon and scholar of how Americans speak. Mencken was committed to American English in all its ways and varieties (called descriptivism by linguists, in contrast to the prescriptivism of the royal academy).

In 1936, he mused in The New Yorker on the words commonly used to name a city’s residents:

The citizen of New York calls himself a New Yorker, the citizen of Chicago calls himself a Chicagoan, the citizen of Buffalo calls himself a Buffalonian, the citizen of Seattle calls himself a Seattleite, and the citizen of Los Angeles calls himself an Angeleño. … In Los Angeles, of course, Angeleño is seldom used by the great masses of Bible students and hopeful Utopians, most of whom think and speak of themselves not as citizens of the place at all but as Iowans, Nebraskans, North and South Dakotans, and so on. But the local newspapers like to show off Angeleño, though they always forget the tilde.2

Mencken hated Los Angeles for its provincialism, which may explain in part why he favored Angeleño, the least common, least Iowan and most musical word to bind a heedless people to their place. Mencken presumed that the tilde (the mark above the n in Angeleño) was an accent mark that careless typesetters forgot. It isn’t. The unfamiliar ñ/eñe (pronounced enyé)—has been a separate letter in the Spanish alphabet since the eighteenth century. (Think of the “nyon” sound in canyon/cañon, although that’s not exactly it either.)

Angeleño to Mencken may have sounded something like ăn′-hǝ-lǝnyō or perhaps ăn′-hǝ-lānyō, with stress on the first syllable which sounded more like awn and less like ann.

Angeleño wasn’t a word residents of Los Angeles would have seen in the Los Angeles Times in 1936. Mencken was right that the most common Los Angeles demonym (the technical term for a place-based name) was Angeleno, without the eñe. The Times spelled it that way in more than 700 articles in 1936 alone (and at least 10,000 times between 1930 and 1950). Angeleno—usually pronounced ăn′-jǝ-lē′-nō—stresses the first and third syllables and sounds like nothing in Spanish.

In picking Angeleño, Mencken, perhaps unthinking, had fallen into the prescriptivist trap. When an expert makes a definitive choice—and Mencken was an expert—it’s understood to be the right way to say something.3

The people of Los Angeles didn’t have the perfect word for themselves even before the diaspora of flat-voweled Midwesterners arrived after 1900. We still don’t have one word that accepts us all.

Disappearing Ñ

A 2015 report to the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission, in a filing to give historical status to an Edwardian-era house, named its location as Angelino Heights, Angeleno Heights and Angeleño Heights almost interchangeably throughout the report. The uncertainty in naming the heights—the city’s first suburb in 1886—layers a sequence of demonyms over the landscape of Los Angeles.

Maps in the late 1880s that parceled out lots on a ridge overlooking downtown were headed with the title Angeleño Heights. The tract’s name became Angeleno Heights in the advertising copy of the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Herald, probably because the decorative typefaces used for splashy real estate ads lacked the eñe character. The Herald did use Angeleño Heights in other contexts after 1886, but not exclusively. The Times used Angeleno Heights in classified ads and news stories, but only a few listings and location references used Angeleño Heights instead.

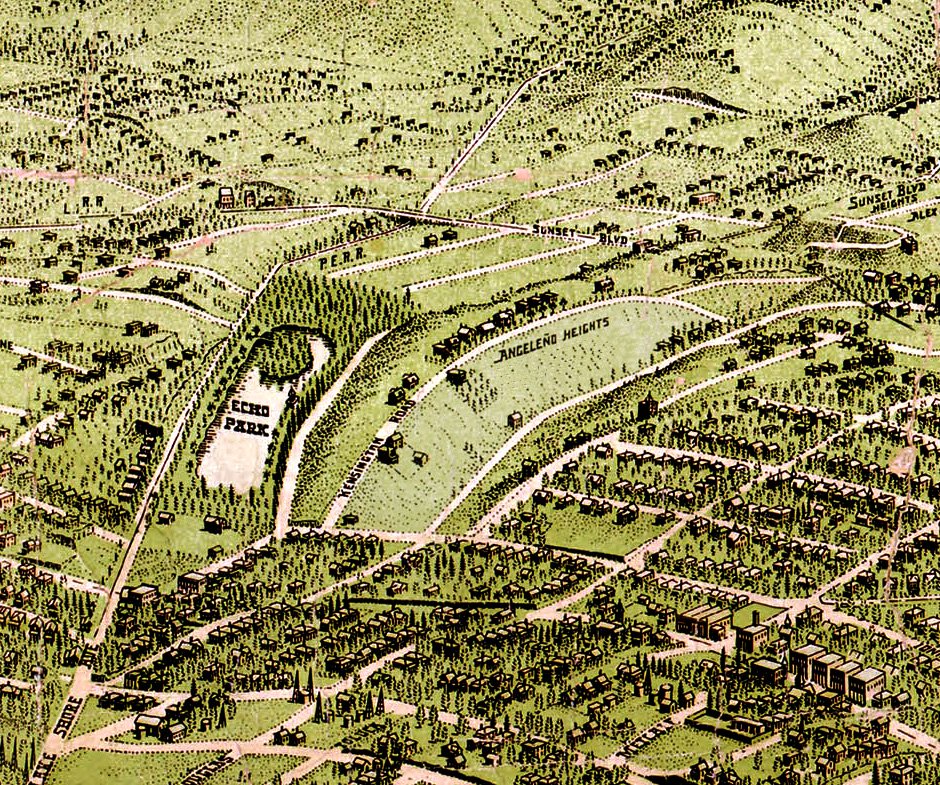

Angeleño Heights, Birdseye View Publishing Co. , 1909

The Birdseye View Publishing Co. rendered virtually every building in Los Angeles on a 1909 map. A block of houses on Kensington Road, even then among empty fields, is labeled Angeleño Heights. By 1918, Angeleño Heights had disappeared. Angelino Heights rarely appeared, except in a few house-for-sale ads, probably typeset that way when the seller telephoned in the ad. It’s an easy error to make when spelling by ear. For English-only speakers, both Angelino and Angeleno will sound the same.

Anecdotal accounts suggest that spelling by ear led city planners in the 1950s to permanently anglicize the neighborhood’s name as Angelino Heights as if they were modern-day Noah Websters reforming an alien word to conform to the speech of the city’s Anglo ascendency.

Highway directional signs continued to point to Angelino Heights until 2008, when Los Angeles City Councilman Ed Reyes had them replaced, correcting the signs, but only to the first, eñe-less error.

Eventually, a truce was called. At Bellevue Avenue and Edgeware Road are two signs that spell out the neighborhood differently: Angeleno Heights is on the highway directional sign; the city’s historic marker uses Angelino Heights.

Stories in a Name

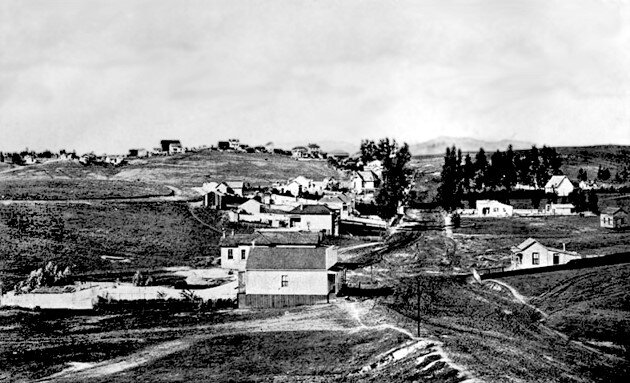

The drift from Angeleño to Angeleno to Angelino back to Angeleno was carried by currents that linger in the story of Los Angeles. In 1850, when the Mexican ciudad de los Ángeles abruptly became the American city of Los Angeles, its tiny Anglophone population was necessarily bilingual in borderlands Spanish. Court proceedings, ordinances and city council meetings were in English and Spanish (and sometimes only in Spanish).

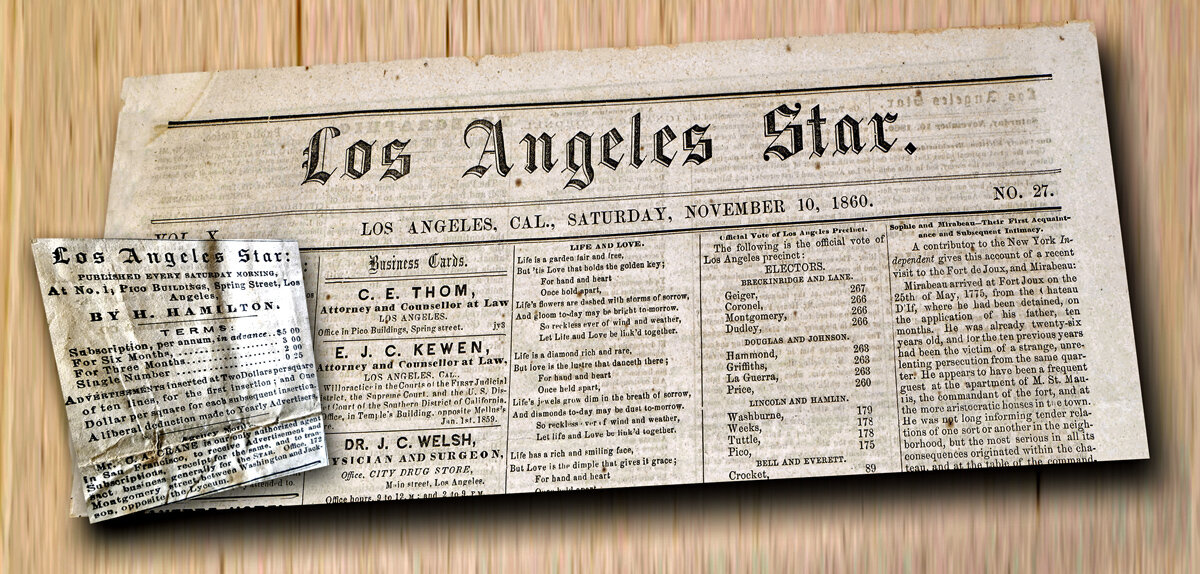

What the city’s Americans called themselves isn’t clear. It may even have been Angeleño. The eñe was still in the type fonts of printers. The Star/La Estrella—the city’s bilingual newspaper—accurately characterized travelers from Sonora as Sonoreños in 1853. But the paper apparently had no collective name for Los Angeles residents, identifying them as Americans, Californians and Mexicans in the English language columns and as americanos, californios and mejicanos/mexicanos on its Spanish pages. El Clamor Publico—the city’s Spanish language newspaper in the 1850s—did the same. (For a differing account, see the epilog below.)

It wasn’t until January 1878 that the Los Angeles Herald described residents as Los Angeleños. By 1880, the Herald had clipped this to Angeleños, a spelling the paper continued to use intermittently with Angelenos (without an eñe) through early 1895. The Herald then carried on without an eñe until the paper merged with the Los Angeles Evening Express in 1921.

The Los Angeles Times was equally inconsistent. In 1882, less than a year after its first edition, the paper was regularly referring to Angeleños collectively. Angeleños (sometimes with “Los”) appeared in news and society columns through mid-1910, a linguistic puzzle for the growing number of residents who had never heard their demonym spoken. But some writers had heard and recorded an echo of the Spanish gentilicio.

In 1888, Walter Lindley and J. P. Widney referenced Angeleños in their popular guidebook, as did Charles Lummis in Out West magazine in the late 1890s. T. Corry Conner’s city guide in 1902 and J. M. Guinn’s history of California in 1907 both used Angeleño to name Los Angeles residents. Harris Newmark—who had arrived in 1853 from Germany and who spoke Spanish as often as he did English in those days—used Angeleño throughout his 1916 memoir of American Los Angeles.

Even as the twentieth century began, the eñe in Angeleño lingered at the margins of the city’s self-image, a fading music. But had it ever actually played?

Orthographic Salsa

In 1948, the Los Angeles Times style guide directed the paper’s copyeditors to reference Angeleno/Angelenos exclusively. Angelino/Angelinos made it into other papers, spelled in imitation of the sound that transplants gave to the last syllable of loss an´-je-leeze (when they didn’t pronounce Los Angeles as loss-sang’-liss).

Angeleno/Angelenos made it into dictionaries—in the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (which gave Angeleño as an alternative), in the third unabridged Merriam-Webster Dictionary (which offered Angelino as an alternative), and in the current American Heritage Dictionary (with no alternate spelling).

Dictionaries that provide word origins point to angeleño and the Spanish eño morpheme as the source from which Angeleno was derived. It makes a neat evolutionary tree. Angeleño (hard for English-only speakers pronounce correctly) begets Angeleno (easier but unclear about the value of the second e), which becomes Angelino (finally pinning down that value).

Except the Angeleño source may be only conjectural. The OED dates Angeleño’s first appearance to 1888 in the Lindley and Widney guidebook. The appearance of Angeleño in the Los Angeles Herald in 1878 pushes back the word’s first use in print, but 1878 is almost a decade after the city ceased to be casually bilingual.

For Robert D. Angus, writing in California Linguistic Notes in 2005, the Angeleño origin story is unlikely, and the word is probably an Anglo invention. Angeleño “appears to be a self-conscious and intentional (but erroneous) emulation of a Spanish looking and sounding form, a kind of fashionable hypercorrection, garnishing an article in a trendy publication like a dab of orthographic salsa.”4

Despite the appearance of Angeleño/Angeleños in contemporary publications in Latin America (and even in the English language newspaper published in the Filipino city of Angeles), each fresh occurrence of the ñ might be another instance of spreading more orthographic salsa. The pull of American English, Angus thought, would naturally end the confusion, and we would properly be Los Angeleans one day.

Who Are We?

Comb through books in English published since 1950 for the names that the people of Los Angeles have been given, and Angelenos tops the other alternatives: angelinos, angeleños and Angeleans. That doesn’t make Angeleno the right (prescriptivist) way to identify us but only the typical (descriptivist) way.

No more right is angelino (with an aspirated g that breathes into the following e: ăn′-hǝl-ēnō), despite the royal academy’s decision to fix our gentilicio. Nor is Angeleño more correct, despite my own attempts (and of some in the Latino community) to foster that name back into use.

Angeleño might be a linguistic myth and a reminder of Anglo nostalgia for the fantasy romance of Spanish Los Angeles, but that the name may be a myth is inconsequential. Angeleño is already in the reality of Los Angeles.

Although we’re no longer Mencken’s tribes of “Iowans, Nebraskans, North and South Dakotans, and so on,” a worse alternative would be two permanently divergent language streams, their Spanish and English histories separated although they share the same place. A Latino resident of Boyle Heights could choose to be an angelino/ăn′-hǝl-ēnō, the Anglo Westsider would always be an Angeleno/ăn′-jǝ-lē′-nō, and neither angelinos nor Angelenos would know the full music of the other, depriving both speakers of some of the hybridizing of Los Angeles.

They would never experience the strangeness that Jesuit philosopher Michel de Certeau thought was necessary to make the everyday more difficult in order to make it more truly felt. They wouldn’t know the many stories of their place and end by not knowing their place at all. “Through stories about places,” de Certeau wrote, “they become habitable. … One must awaken the stories that sleep in the streets and that sometimes lie within a simple name.”5

Los Angeles existed first in the mouth. It was spoken before it was. It was inhabited with words before it was lived in by us. In the process, Los Angeles has gathered many names. All of them have entered into language and the imagination and thus into history. Angelino, Angeleno and Angeleño (even Angelean) are part of who we are, part of our sense of self and of place.

We’re all those names.

Epilogue

Angelenos responded to Morrison’s column in the Los Angeles Times. One commentator (with the screen name dckimbrobills) found further instances in post-1850s Los Angeles of Angeleño, Angeleno, Angelino and compared these with usages in Spanish speaking countries.

[P]eople living in Madrid are indeed called “Madrileños,” just as residents of Quito are called “Quiteños,” and residents of Lima are called “Limeños (both Lima Peru and Lima El Salvador), so the resident of Los Angeles could quite naturally be called Angeleños. … In Los Ángeles, Chile, the terms angelino and angelina are used.

Dckimbrobills also searched the databases of the city’s bilingual and Spanish language newspapers.

In 1875 there was an announcement about a concert for the benefit of "el pueblo angelino." Likewise, in 1875 someone wrote of "F. P. Ramirez" as one of the luminaries of "el foro angelino." In 1921, Aurielio Castro of Santa Barbara wrote about a newspaper in Los Angeles as "el diario angelino." There is even one instance in 1876 where the phrase "el angelino" was used seemingly in the modern sense.

But the English-only newspapers of the period reflect a different demonym.

Most interesting is that if you search English language newspapers in Los Angeles between 1855 and 1922, the tern Angeleño shows many times, mainly in the Los Angeles Times. … [The] Los Angeles Daily Evening Express (1875 - 1877) had dozens of articles where the term not just Angeleño is used, but Los Angeleño and even East Los Angeleño (that is, residents of what is now Lincoln Heights).

This divergence gives support to Robert D. Angus’ contention that Angeleño may be an invention of the Anglo mythologizers of Los Angeles.

-------------------------------------------------

Notes

1. “El gentilicio correcto de Los Angeles es angelino,” https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/el-gentilicio-correcto-de-los-angeles-es-angelino-GKDL4976, accessed 01 February 2019.

2. H. L. Mencken, “The Advance of Municipal Onomastics,” The New Yorker, 08 February 1936, 54-57.

3. Mencken’s The American Language: A Preliminary Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States went through multiple editions after its publication in 1919.

4. Robert D. Angus, “Place name morphology and the people of Los Angeles,” California Linguistic Notes, vol XXX, no. 2, fall 2005.

5. De Certeau, Giard, Mayol; Timothy Tomasik, trans., The Practice of Everyday Life: Volume 2: Living and Cooking (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 142-143.

Publication note. This essay is adapted from “Who Are We” (LMU magazine, Spring 2019) and “Who Do You Say I Am?” in Becoming Los Angeles: Myth, Memory and a Sense of Place (Angel City Press, 2020).

Seal of Amnesia

How do you draw forgetfulness?

Seal of Amnesia

How do you draw forgetfulness?

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in 2004 decided to erase the Latin cross that former Supervisor Kenneth Hahn had put on a redesigned county seal in 1957. A divided board voted to edit out the disturbing imagery and made other changes in Hahn's seal. The mythical goddess Pomona was replaced by a Native American girl. Oil derricks were swapped for the mission church of San Gabriel Arcángel.

As Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky pointed out in a 2015 Los Angeles Times editorial, the mission was depicted without a cross. The board majority, he said, wanted it that way in 2004. Other supervisors remembered differently. The cross had fallen during the 1997 Northridge earthquake. It’s lack on the county seal had been for accuracy.

In 2014, another divided board decided to put the Latin cross back on the seal as an addition to the façade of the mission for, it was now said, historical accuracy. Soon after, the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which had urged removing the original cross, sued the board to turn back the seal to the cross-less 2004 version.

In her ruling upholding the ACLU suit, U.S. District Judge Christina A. Snyder wrote that the “change and the associated expenditure of public funds places the county’s power, prestige, and purse behind a single religion, Christianity, without making any such benefit available on an equal basis to those with secular objectives or alternative sectarian views.”

The judge’s ruling, which the board declined to appeal, ended Yaroslavsky's naïve hope that "Our county seal should be a unifying emblem that all Los Angeles residents can call their own ..."

In Los Angeles, a place notable for edited lives, a symbol that tried to unify who we are would have to picture the unimaginable. We're so impatient with other people's memories and so careless with our own. How do you draw forgetfulness?

Corporate America learned long ago that your misinterpretation of their symbols isn't good for business, as Proctor and Gamble discovered when some Christian zealots in the 1970s imagined satanic references in that company's corporate symbol. Proctor and Gamble adopted a new, innocuous logo.

For the makers of advertising nonsense, a product name should be meaningless sounds, and the company emblem should be a conundrum. Did the name Enron identify a power company or an erectile dysfunction preparation? The company's cockeyed E logo refused to own up.

For the people in marketing, the name Enron had whatever meaning the company said it did, and if the company's product ultimately failed, it could be branded with a different string of optimistic consonants and vowels and another bit of askew typography.

The Board of Supervisors should have learned Proctor and Gamble's lesson. The iconography of the county seal contains appeals to a past we don't want – to Pearlette the award winning heifer, an unnamed tuna fish, and drafting tools. These obsolete markers of our former prosperity mock what we used to think of ourselves.

Calligraphy by Kanjuro Shibata, "Ensō (円相)"

The cross should stay off the county seal because, among other things, the cross stands for the risks of believing in something. Putting one there would be a lie about Los Angeles. An officially sanctioned reminder of any sort of faithfulness is the last thing we want.

Scrap the galleon San Salvador, which Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailed into San Pedro Bay in 1542, for its imperial presumption. And take down the cross-less mission church, symbol of Native American genocide to many.

Better to scrape off the name "Los Angeles" for its religious and colonialist overtones.

The county's corporate name should be Elā – two meaningless syllables, pronounceable in most of the 185 languages spoken in the county, short, and sort of uplifting without promising anything the Federal Trade Commission would question. The imagery on the county seal ought to be pointlessly assertive, celebrating action without purpose. Too bad the Nike swoosh is already taken.

But if our place can't be boiled down to a trademark and a made-up word, perhaps it could be represented by all of us instead.

Draw something like on odometer on the seal, the numbers in the total rolling up from 10,000,000 as the county's population increases. New numbers could be stenciled on county buildings every year, memorializing nothing except the bare fact of our existence.

Or the seal could be replaced by a mirror so that you'd see only your own image, the one thing that apparently matters. Nothing else endures the withering fury of our grievances against the past. The county seal should reflect only our own self-regard.

Or everything should come off, because collectively we have neither the courage nor the humility to deal with the history that the seal represents. Public symbols should be neutral surfaces, untroubled by what we've been and uncomprehending of what we might become, because we resist the idea of becoming anything together.

In Encino, light, more light

Originally published in arcCA 03.4 as “Reflect Renew.”

In Encino, light, more light

Originally published in arcCA 03.4 as “Reflect Renew.”

A specific volume of light

Walk north on Balboa Boulevard from the commercial hurly-burly of Ventura and within 200 feet you’re deep in the suburban grid that consumed square miles of San Fernando Valley chicken ranches and orchards in the 1950s. Today’s landscape looks domesticated, but the light is for a desert, simplifying everything into glare or shadow.

By 10 a.m. on this Sunday morning in August 2003, the milky sky is incandescent and the valley heat is already a material presence. What you need is shelter. What’s available is mostly nostalgic, given that virtually everyone here is or was an immigrant and full of longing.

The campus of the First Presbyterian Church of Encino, a block up from Ventura Boulevard, replicates an immigrant’s longing and some of longing’s provisional remedies. The original church from 1945 is a vaguely English, half-timbered shed constructed, one parishioner told me, with the help of the actor Edward Everett Horton. Attached to it is a more substantial block of classrooms and offices that implies an abbey cloister.

(By 2022, the original church had become the Kehillah Chen v'Chesed Jewish Universalist congregation.)

The second church, put up in 1954, still suggests British roots with a shorthand of historical detail applied to the exterior of a simple, A-frame structure. There are hundreds of churches like this in mid-century neighborhoods, evoking traditions on a framework of everyday modernism.

But it’s too bright to stand outside considering how Los Angeles makes the modern look traditional. You want shade.

Step inside the nave and what you get is more light. It’s light with a remarkable emotional range and almost always presented – even when artificial – with great subtlety and sophistication. It’s never unmediated light. It’s light that’s passed through something, been cut by asymmetrical openings, allowed to screen on a tilted and curving panel, been half blocked by the overlapping edge of another panel, let in to gather in irregular polygons from 14 mostly unseen skylights, been reflected onto white oak pews and absorbed by the gray of the carpeting and the black concrete of the chancel platform.

It’s as if you had taken a platinum photographic print and enlarged it to wall size blocks of tones graduating from not exactly white to not quite black.

Award winning church interior

(This luminous interior earned the AIACC Honor Award for Design in 2003. Apart from the astonishing beauty realized by principal architects Trevor Abramson and Douglas Teiger and Michael Cranfill, architect in charge of design of the remodeled interior, the work took just seven months to complete and cost less than $900,000.)

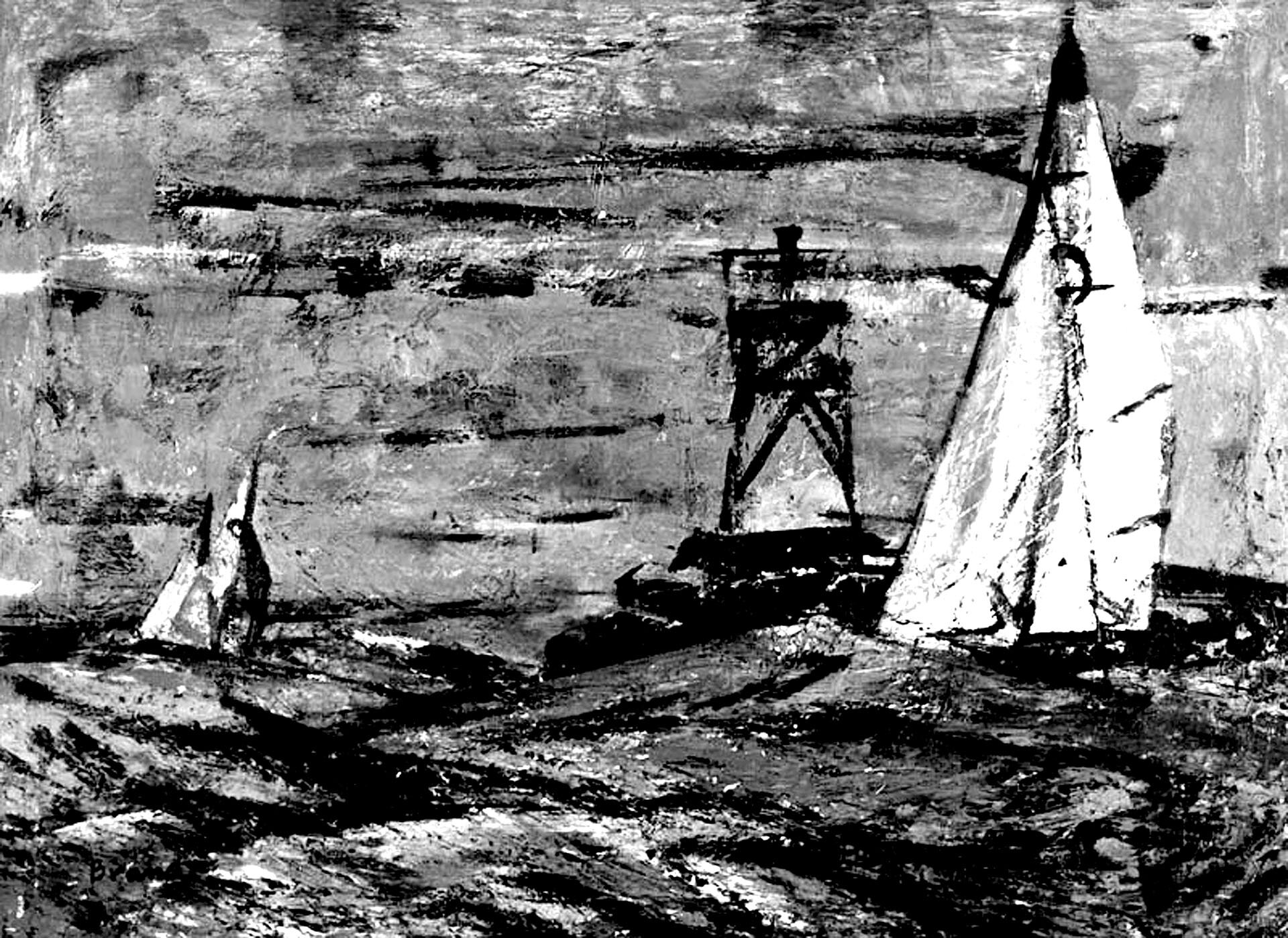

The pervasive, ambivalent light all around you isn’t static. The succession of tones modulates minute by minute as the morning sun climbs and follows the ridge of the roof, turning the recesses of the east facing chancel wall into a gallery of monochrome abstractions. A comparable experience – interior light as theology – is in the church paintings of the 17th century Dutch artist Pieter Jansz Saenredam. He caught the pale northern light pouring over Gothic pillars and arches from the clear windowpanes that had replaced the stained glass in the stripped and whitewashed naves of Catholic cathedrals made Calvinist. Saenredam painted the undeceiving light of reformation.

When an usher, working the controls before the service, extinguishes the spotlights that define the oval plinth and its incised cross in front of the chancel and the 16-foot-high cross that projects into it, the remaining daylight is less dramatic. It’s more nuanced in shades of gray, more capable of affirming the physical surface of the plaster-over-sheetrock of the large side panels, in that way more architectural, and even more mysterious (and less liturgical) as the light passes over the planes of the chancel wall.

Whatever it might be in the abstract as space for manipulating light, this sanctuary is a machine for praying in a particular way. With the spotlights back on and the service begun, the worship space reorganizes around the hulk of the grand piano accompanying the hymn tunes and the officiant at the ambo reading aloud the words of the Gospel. There is a parallel text in the light animating the panels that bend and clasp over his head.

The optimistic lesson of the First Presbyterian Church of Encino is that a lyrical, humane postmodernism is a fit alternative to nostalgia in making sacred spaces in Los Angeles. Hundreds of suburban churches from the 1950s, crowded with immigrant shadows, await a new enlightenment.

Hody’s Family Restaurant

Lakewood Boulevard at Candlewood Street

Hody’s Family Restaurant

Lakewood Boulevard at Candlewood Street

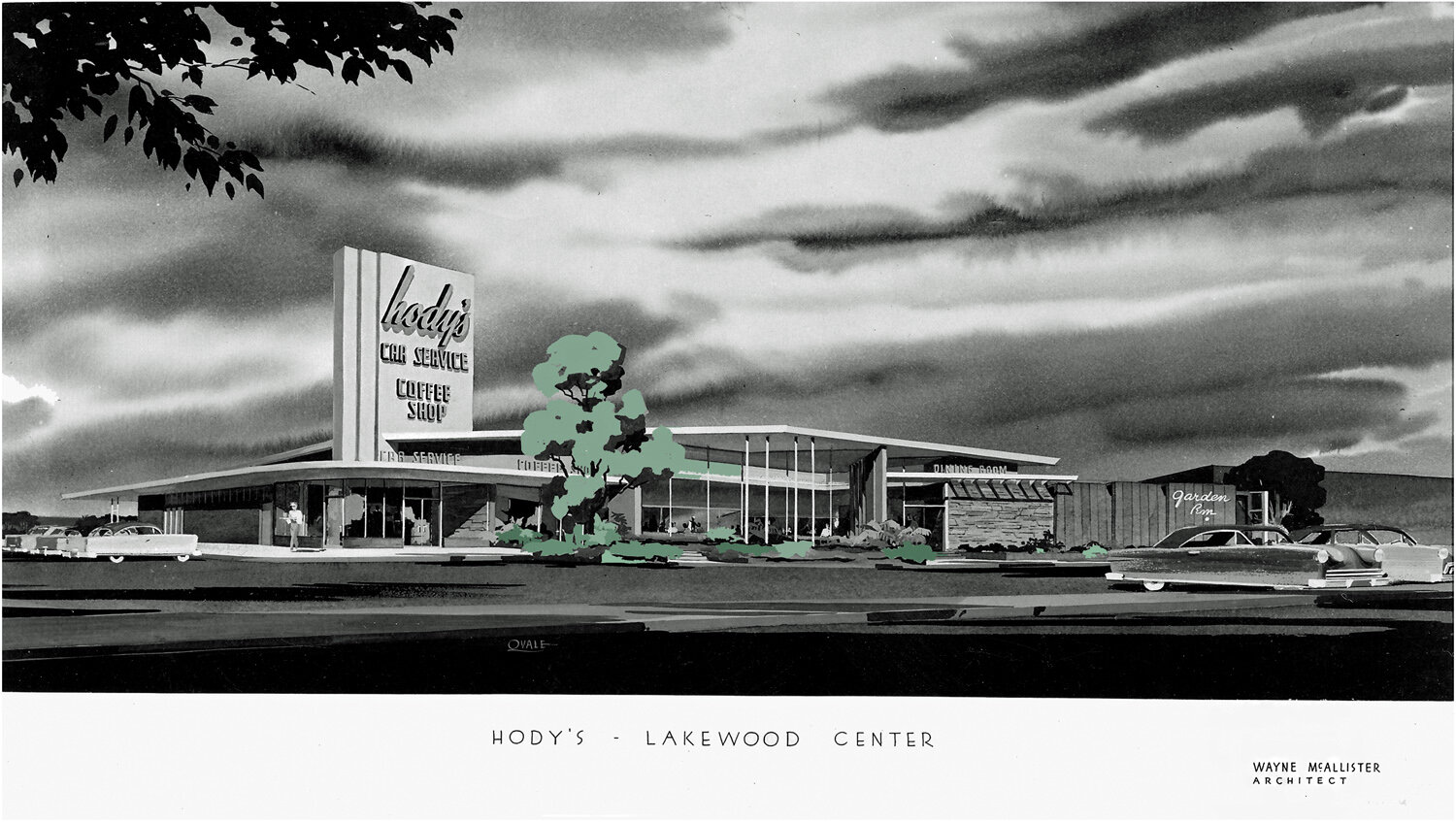

Hody’s Family Restaurant in 1952 was toffee and caramel stucco on the outside and wood veneer and red vinyl in the half-dark interior. Somewhere inside even darker, there was a cocktail lounge. Hody’s tower gestured toward the boulevard that pointed north across the dead-level landscape between Lakewood and Pico Rivera. Cruising teenagers might swing over to Wallach’s Music City, play 45s in a listening booth, and then pull into Hody’s in Lakewood Center for burger and a coke.

Kids’ menu

Hody’s was, the local newspaper said, designed inside and out by Wayne McAllister. He would become famous for Southern California’s Googie-style coffee shops. The Lakewood Hody’s was more restrained, because restauranteur Sidney Hoedemaker wanted it that way.

Hody’s made the transition for my neighbors from diner to a sit-down restaurant with cloth napkins, but the restaurant also had counter service and car hops. It was still not middle class.

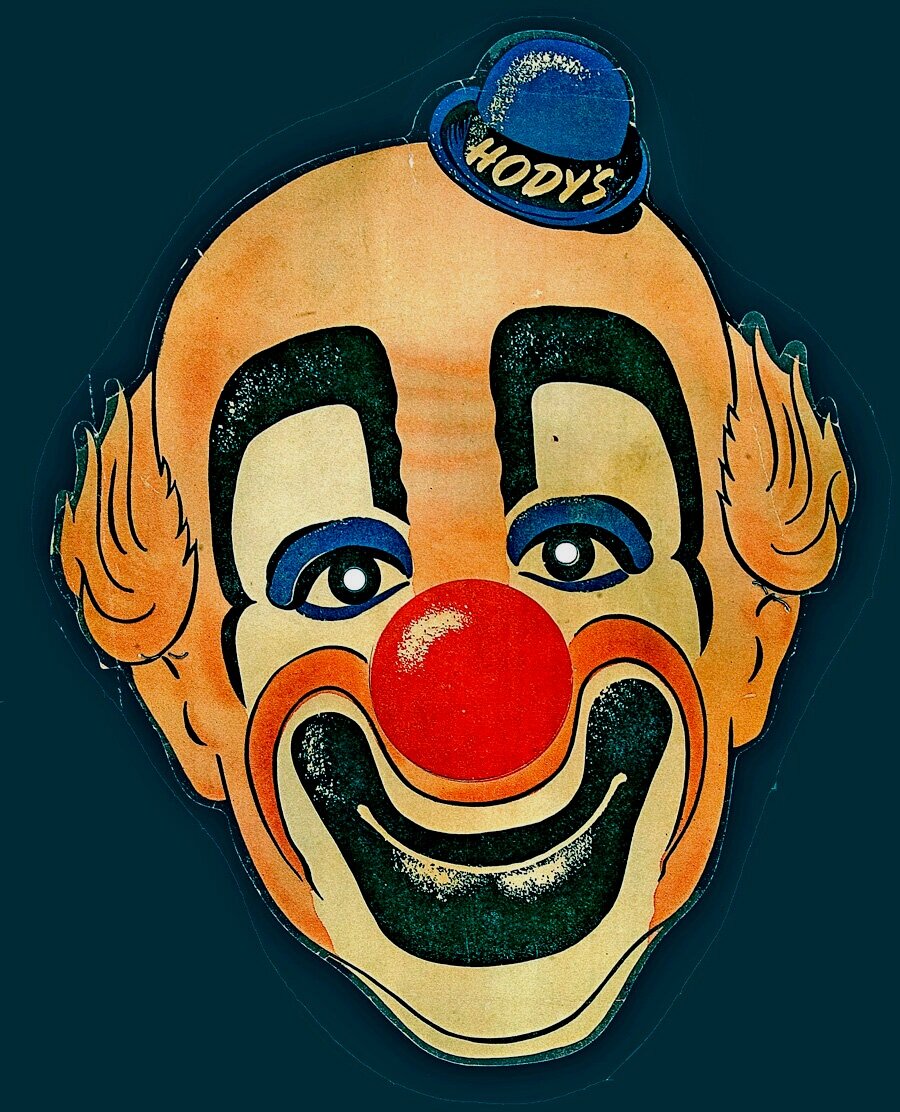

I remember best the dried seahorses and starfish entombed in the plastic dividers between the booths and the horrific, clown face menu for kids.

I have no memory of the food, except the intense tomato redness of the viscous French dressing they served on salads. It was both astringent and too sweet, rather like our lives then.

Hotrods and Hedonism

Creating the California Sublime in post-war Los Angeles

Hotrods and Hedonism

Creating the California Sublime in post-war Los Angeles

In September 1945, under a pall of ocher smog, Los Angeles entered the postwar world. The city was bigger than it had been when the war began, wealthier, and more diverse. Its established people—past middle age and conservative; few who were really rich—kept the narrowness of the Midwest towns from most of them had come. The city’s new people—Okies and Arkies, Black Southerners, and white ethnics—had arrived with the buildup to war. Few of them had much interest in art.

There was art in Los Angeles they could have seen. Broad-shouldered men and women in WPA murals reaped and forged and lifted up symbols of a better America to come. Sabato Rodia’s unfinished Watts Towers/Nuestro Pueblo glittered over the Pacific Electric tracks south of downtown. In office waiting rooms, in the bank lobby, and on sale at Barker Brothers were desert landscapes with chaparral and scenes with eucalyptus trees and poppies. The paintings were loosely impressionist in a taste that had grown stale.

At the county’s Museum of History, Science, and Art—its name a hierarchy of values—curators mounted loan exhibitions among the mastodon skeletons. The Huntington Library displayed a superb collection of eighteenth century portraits and landscapes.

Serious collectors of modern art could find Matisse and Picasso, Klee and Kandinsky at Earl Stendahl’s gallery on Wilshire Boulevard and Frank Perls’ gallery nearby, but Stendahl and Perls were practically alone.

Abstract art. Mrs. Rudolph Polk, vice president of Los Angeles Municipal Art Commission, views “Image” by Esther Rohr, which won $100 prize at All City Outdoor Art Festival in 1956. Photograph courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library, Valley Times Collection

The Chouinard Art Institute, the Art Center School, and the Otis Art Institute offered day and evening art classes for veterans studying on the GI Bill. (Some would get jobs cartooning for Disney or Warner Bros.)

Art—as a way of life and a livelihood—was something found in New York that September. Los Angeles didn’t even have an art museum and it had no interest in opening one. Downtown and Hollywood were separate Protestant and Jewish worlds; their moneyed people never mixed.

With a few exceptions—Man Ray was the subject of two retrospectives in the 1940s—little public notice was taken of contemporary art. Officially, Los Angeles distrusted art that delivered the shock of the new.

On Olvera Street in 1932, city workers had whitewashed America Tropical, David Alfaro Siqueiros’ allegory of American oppression. In 1939, conservatives on the county museum board had turned down a gift of avant-garde works from the collection of Walter and Louise Arensberg. Vincent Price, Edward G. Robinson, Fanny Brice, and Sam Jaffe founded the Modern Institute of Art in 1947 to keep the Arensberg collection in Los Angeles, but the institute closed when funding ran out. The art went to Philadelphia in 1950.

Indifference had turned into hostility. When James Byrnes, the first curator of modern and contemporary art at the county museum, sought a Jackson Pollock painting in 1947, he was told by one of the museum’s trustees to keep the painting out of sight in his office.

Culture war

Anne Bartlett Ayres in the catalog for the exhibition Art in Los Angeles: Seventeen Artists in the Sixties described the city in 1950 as “(v)ulgar, extroverted, spontaneous, energetic, proudly unsophisticated—Los Angeles discouraged a civilized sense of art historical continuities.” It also seethed with resentments.

Kenneth Ross, the director of the city-funded Municipal Art Department, had a pragmatic approach to art in Los Angeles, drawn from New Deal models of communal action. Art, film, dance, and music—without much discrimination except that it should be lively and interesting—could be brought to every Los Angeles neighborhood, even to communities of color. In his way stood the politics of mid-century Los Angeles, a mixture of anti-immigrant, anti-modern, anti-Communist, and anti-New Deal sentiments that flowed through the influential California Art Club to city council members equally unsettled by manifestations of the new.

The club and its city council allies tried to block Ross’ appointment as department director, only to be overruled by the Municipal Art Commission in 1949.

Ross hoped his eclectic approach would accommodate every taste (and quiet some of the criticism). The All-City Outdoor Arts Festival he planned for 1951 was two weeks of community engagement held at parks and at the Greek Theater. Dance and music performances were included, but the focus was on the jury’s selection of 180 paintings and sculptures in a wide range of styles, including art that was influenced by surrealism, cubism, and abstract expressionism.

That was too many “isms” for traditionalists. As Sarah Schrank notes in Art and the City: Civic Imagination and Cultural Authority in Los Angeles, Ross’ critics used the Los Angeles Times to complain of the art and Ross’ politics and patriotism. The San Fernando Valley Professional Artists’ Guild and the Coordinating Committee for Traditional Art went directly to the city council. Ross, they wrote, championed “Communist art” and besides, there weren’t enough of their own members’ works in the festival.

When City Councilman Harold Harby convened the first of two days of a noisy public hearing intended to condemn the festival’s “offensive and nauseating” modern art, a member of the Society for Sanity in Art smeared non-representational works in the festival as “meaningless lines and daubs with nothing that is uplifting or spiritual, only an affront to the sensibilities of normal people.”

Other speakers informed the city council that modern art was unhealthy, dangerous, and perverse. Harby thought the works were “Communistic” in spirit (if not actual Soviet propaganda). He singled out an abstract seascape by Rex Brandt, one of the festival award winners, pointing to a hammer-and-sickle he saw in one boat’s sail.

Harsh questioning of one of the festival’s artists drove him to tears. He had spent, he said, “two years in the Army fighting for freedom of expression.”

Propaganda or a seascape. Councilman Harold Harby concluded that “Surge of the Sea” by Rex Brandt included a hammer and sickle design on the sail on the right. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library, Herald-Examiner Collection

The conflict was partly generational. Art club members were older, genteel, and conservative. The contemporary painters were mostly former servicemen, brash, young, and uninterested in uplift. The dispute was also about the city’s other concerns: the passing of cultural authority to new Angelenos and the unmet aspirations of Latinos and African Americans. A plein-air painting wasn’t about a pretty landscape. It was about how you imagined Los Angeles should be.

The second day of hearings, coming a week later, only deepened the confusion between aesthetics and politics. In the report submitted by Councilman Harby (along with Charles Navarro and John Gibson), the festival’s non-representational art was branded as anti-American.

Although the city council ultimately resisted this interpretation, along with Harby’s demand for a separate show for “sane” art, city council members did compel Ross to submit his budget to additional oversight. In the future, Ross would have less freedom to present an inclusive festival.

The politics of modernism had split the city council along the same lines that was dividing it over the issue of public housing. When Harby helped Norris Poulson become mayor in 1953, running on a platform that opposed public housing, Ross’ position as department director became even more difficult. His business sponsors drifted away, fearful of being red-baited.

Sheen and surface

The local culture war was serious enough, but the conflict was fought in a tiny arena around the merits of the European avant-garde and New York abstract expressionism. The real preoccupation of post-war Los Angeles was the popular culture being made and consumed in the city’s new suburbs.

In the tract house valleys and flatlands, young guys with a knack for tinkering were turning twenty-year-old jalopies into chromed and lacquered hot rods. Surfers were taking jet-age materials and giving their boards sleek contours in polymer and fiberglass. Aerospace workers were learning the skills of vacuum forming, acrylic casting, and vapor coating. The sheen of finishes applied to sheet metal and plastic turned industrial objects into objects of desire.

The things the men made were loud, fast, and colorful. They jostled competitively with the stuff of suburban life—billboards shouting come-ons, men’s magazines lingering over every airbrushed inch of skin, local TV recycling vintage Hollywood—and all of it pouring into suburban Los Angeles in an unfiltered torrent of immediate and mostly disposable content.

In a media-saturated city, Spade Cooley, Bill Haley, and the Metropolitan Opera all played on the kitchen radio. The latest issue of William Randolph Hearst’s House Beautiful on the Danish Modern coffee table assailed the abstract expressionists but also warned middle-class housewives that their tastes needed to be modern. Their kids furtively passed around copies of Mad Magazine and Tales from the Crypt, lingering over four-color graphics that rendered the suburban everyday as satire or horror.

The shock of the new. Councilman Harold Harby compares a drawing by a mentally disabled artist with “Bird in the Moon” by Edmund Kohn, a proposed gift to the city by Howard Ahmanson. “If this is a bird,” said Harby, “the moon can have it!” Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library, Herald-Examiner Collection

From this bricolage, the popular culture of postwar Los Angeles rose, part corporate product and part do-it-yourself assembly in which all the arts—high and low—were mashed up and extruded. Los Angeles had impulsively disposed of its own past and long ago made self-invention its defining tradition. The new popular culture and Los Angeles were made for each other. It was an egalitarian, ahistorical, and optimistic fabrication of what the future should be, with all the excess and aspiration that implied.

The rest of the country wondered if art from Los Angeles had anything to say other than well-advertised dreams. Seen from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Los Angeles looked like a mess of clichés: happy, sun-besotted, trivial, and too immersed in spectacle to make serious contemporary art. In Los Angeles, no one seemed to care, even though the shallowness was at least partly true.

In New York in the 1950s, you looked to history and theory to explain how the fears and longings of the age were to be expressed. In Los Angeles, you only had to look to wanton desire. Los Angeles—a bipolar city of bright surfaces sharply bounded by shadows—tended to eroticize everything, to give even the banal a Dionysian spin into play, physical perfection, violence, altered states of consciousness, and a thirst for the infinite.

The infinite had been a part of the sales pitch for Los Angeles for a long time: in its light, its deserts, its emptiness, and its location at the end of the continent. Ecstatic religion, New Age thought, and UFO cults had once satisfied the ordinary folk who wanted transcendence. In a rapidly changing Los Angeles, dabbling in LSD and Zen satisfied some of those who looked for a personal cosmic doorway.

Los Angeles itself was a doorway for guys who liked to draw, who liked to gamble, who dropped in and out of art school, and who didn’t fit in well. Guys like Ed Kienholz, one of the founders with Walter Hopps of the Ferus Gallery in 1957, where Kienholz later showed Roxy’s, the first of his life-size environments assembled from the city’s junk. And guys like Billy Al Bengston, who experimented with industrial pigments and spray lacquer to render luminous hearts, irises, and sergeant’s stripes. And Kenneth Price, who put the same gloss on ceramic pieces, joining traditional craft work to functionless abstraction. And Craig Kauffman, who began painting in a West Cost expressionist style but who is best known for perfectly finished panels of Plexiglas. And John McCracken, who brought the same perfection to resin-coated planks, casually propped against a gallery wall. And Robert Irwin, an intensely focused minimalist in painting and later a fabricator of sight altering installations made solely of light.

If Los Angeles was fundamentally insubstantial, then its art could be limitless light and space and sheen—what the critic Rosalind Krauss would later call “the California Sublime.” And if the city was a less-than-innocent joyride, then Los Angeles artists would cram all of this emerging culture in the back seat.

In Los Angeles, no critical arrow pointed the way. In Los Angeles, there was no art history exam to be passed. You were on your own. Successful New York artists fitted their work into a system of reputation merchandizing that involved certain galleries, art critics, and publications. None of that was true of Los Angeles.

To drum up patronage for their struggling galleries, some artist-entrepreneurs set up courses on contemporary art in Westside living rooms—Tupperware parties for the aesthetically curious. New art was risky, and it didn’t pay in Los Angeles. But the surfing was good, almost everything was cheap, and anything was possible.

An unruly hybridization of the ordinary and the visionary gave a specifically Los Angeles context to the abundance of Andy Warhol’s soup cans (first shown at the Ferus Gallery in 1962), the moral outrage of the Peace Tower (a Vietnam War protest coordinated by Mark di Suvero in 1966), and the ethnic manifestos in Chicano art (itself an extension of labor organizing). Art in Los Angeles could be vulgar or political or intensely private, just like Los Angeles.

Los Angeles artists assembled from light, space, color, adolescence, joy and the debris of the city a body of work that investigated and delineated what Los Angeles meant when it was on the verge. Some observers saw the birth of a new capitol of art in that. Some saw only the shine on too perfect surfaces. Hardly anyone saw the fire that would burn the heart out of these daydreams. Hardly anyone saw that Watts and the rest of Los Angeles was on the verge of 1965.

‘It’s immaterial where you are’

The afterword to Common Place. The American Motel

‘It’s immaterial where you are’

The afterword to Common Place. The American Motel

An adaptation of the afterword to Common Place. The American Motel by Bruce Bégout. Colin Keaveney, trans., Otis Books | Seismicity Editions, 2010.

The parenthetical references are to the pages in Lieu commun: Le motel américain (Editions Allia, 2003).

Bruce Bégout is a French philosopher, writer, and translator who teaches at the Université Bordeaux-Montaigne. A phenomenologist of the everyday, Bégout has examined Las Vegas, American motels, and suburbs as part of an “archeological inquiry into the meanings of our daily urban world.”